Living donor liver transplantation in Brazil—current state

Introduction

In the 80s, with the development of new imunossupressors (calcineurin inhibitors) and surgical skills improvements, the results of deceased donor liver transplantation (DDLT) improved significantly. Subsequently, the number of indications of liver transplantation (LT) increased markedly, exceeding the number of DDLT performed. Therefore, it raised a huge relative organ shortage in the Western and, because of cultural issues, there is no deceased donor in the Eastern.

In this scenario, living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) emerged as an alternative strategy based on liver features. Liver anatomy consists of independent functional units with independent vascular inflow and outflow and biliary drainage that allows it to be divided in two or more functional parts (1). Still, liver has the ability to regenerate, reaching 90% of its total initial volume in a few months (2). Thus, few authors tried to perform experimental LDLT in animal model in the mid-60s (3,4). However, it was only in December 1988 that Raia et al. performed the first clinical LDLT in a 4-year-old child with biliary atresia using an adult left lateral liver graft, unfortunately with a short 6-days survival (5). In 1989, Strong et al. ended up performing the first successful LDLT in a 1-year-5-month-old child with biliary atresia using also an adult left lateral liver graft in Australia (6). Thereafter, numerous centers, mainly in USA and Asia, started developing LDLT in an effort to diminish waiting time and patient mortality on transplantation waiting list.

Currently, LDLT is a well-established procedure with about 20,000 transplants per year worldwide. Moreover, it brought surgical skills and scientific improvements in LT clinical practices, being regarded as an excellent LT strategy in regions suffering from organ shortage like Brazil (7,8). In this paper, we report Brazilian experience in this modality of LT.

Methods

Data was collected from Brazilian Organ Transplantation Association (ABTO). Since 1997, ABTO has published annual reports concerning national organ donation, solid and non-solid organ transplantation. We also searched PubMed using the search terms “LT”, “living donor” and “Brazil”. All Brazilian experience reports and original articles were selected. They were excluded articles whereas a more recent update data had been published.

Results

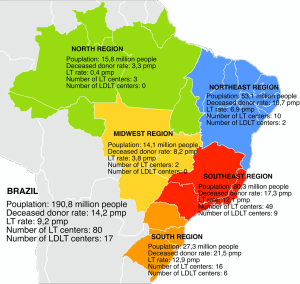

Nationwide, 17 LT centers presently perform LDLT (Figure 1). The majority is spread in the southeast and south regions, representing 15 centers. Overall, 9 centers perform adult LDLT, 6 centers pediatric LDLT and 2 centers both adult and pediatric ones (9).

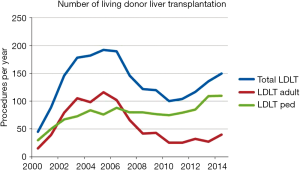

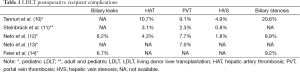

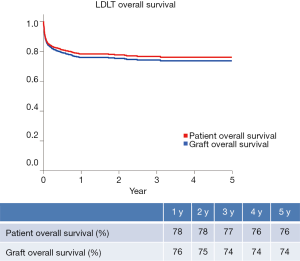

Until December 2014, 2086 LDLT procedures have been performed, whereas 42.2% and 57.8% of them represent adult and pediatric ones, respectively (Figure 2) (9). Postoperative recipient complications are described in Table 1. Up to 2006, both patient and graft national overall 1-y survival were 72.5%, and patient and graft national overall 5-y survival were 65.6% and 62.9%, respectively. Currently, patient national overall 1- and 5-y survival represent 78% and 76%, and graft national overall 1 and 5 y one 76% and 74%, respectively (Figure 3) (9). Retransplantation rate after primary graft nonfunction or/and hepatic artery thrombosis accounts for 11.44%, with an overall 60-d survival of 61.77% (15).

Full table

Donor morbidity ranges from 12.4% to 28.3% (10,16-21). Most of them are minor complications, such as abdominal pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, minor bile leaks and superficial surgical infection. Biliary tract injury—biliary leak and/or biloma—is observed in 2.5% to 8.3% of the donors and up to 20% of them need any kind of invasive treatment, which represents Dido-Clavien classification grade III (22). Among others Dindo-Clavien grade III complications, Wiederkehr et al. (18) reported one case of biliary stenosis among 132 liver living donors. Coelho et al. (17), in a 60 right-lobe LDLT series, described 1 case of perforated duodenal ulcer. The donor ended up going to surgery because of abdominal pain and sepsis on 3rd PO and progressed to septic shock and multiple organ failure thereafter. He was discharged on 68th PO with hemiparesis secondary to severe hypotension and cerebral ischemia.

Seda-Neto et al. gave special attention to segment IV complications after left lateral hepatectomy harvesting. Among 204 donors 10 developed segment IV necrosis or abscess and 4 of them had had segment IVB resection intra-operatively. The rest were readmitted 2 to 30 days after being discharged with abdominal pain, dyspepsia and/or fever. Five patients underwent CT-scan percutaneous abscess drainage. All were treated with IV antibiotics and none of them needed further surgical management.

Comparing 63 right living donor hepatectomy for adult LDLT and 60 left lateral one for pediatric LDLT, Steinbrück et al. (19) found no significant differences regard postoperative complication based on Dindo-Clavien grading. However, biliary complication (Dindo-Clavien grade 3A) was seen in 10 donors, 9 of them in right hepatectomy donors (P=0.01), which is probably consequence of a greater liver cut surface in the remnant liver. Also, three left lateral hepatectomy donors presented with gastric volvulus (Dindo-Clavien grade 3A), all treated by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy.

Three deaths have been reported in Brazil, representing a mortality rate of 0.14% (9). One donor was a 31-year-old female who underwent a right-lobe harvest. She presented a cerebral hemorrhage on 7th PO while recovering from mild liver failure (INR of 1.75 and bilirubin level of 3.5 g/dL). CT-Scan showed a subarachnoid hemorrhage with no evidence of cerebral edema (18). Another donor was a 36-year-old female who also underwent a right-lobe harvest. After 4 hours of surgery, she presented with hypoxia and tachycardia followed by cardiac arrhythmia and cardiac arrest. She recovered after 10 min of cardiopulmonary advanced resuscitation, but unfortunately 2 days later a cerebral arteriography confirmed the diagnosis of brain death. At autopsy, neither thromboembolism nor myocardial infarction was identified. She had no previous history cardiopulmonary disease (17).

Discussion

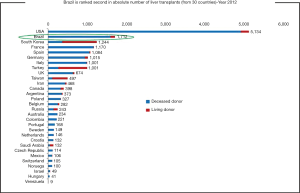

Brazil has a resident population of 190.8 million and there are about 4,800 people waiting for LT across the country. Although Brazil ranks in the second place in number of LT procedures per year worldwide, only 36% of the estimated demand of it was done in 2014 (Figure 4). These numbers reflect the organ shortage challenge facing Brazil, which sees in LDLT a good option to overcome it.

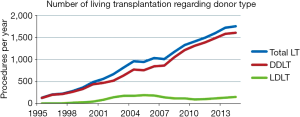

Nowadays LDLT represents about 8.5% of LT procedures nationwide. Prior to 2001, more than 50% of them were pediatric one. At the beginning of 21st century, LDLT grew exponentially, reaching a peak of 192 procedures per year in 2005. At this moment, LDLT represented 19.7% of all LT procedures. However, since that two distinct courses can be seen comparing adult and pediatric recipients (Figure 5). After changes in organ allocation policy in 2006—introduction of MELD—and international reports of living donor deaths, adult LDLT significantly diminished. Currently, 17 centers perform LDLT, whereas 15 are located in southeast and south regions, mainly pediatric LDLT, representing 76–80% of all LDLT, mostly from related donors.

Overall, biliary complications have been the leading cause of postoperative recipient complication in LDLT, ranging from 15–60% and 15–40% in adult and pediatric LDLT, respectively (14,23). According to Brazilian centers’ publications, this is also the most common recipient complication. It ranges from 6.2% to 20.6%, most of them biliary stenosis, and is associated with increased hospital stays and cost (10,12,14). In attempt to decrease and/or early diagnose this type of complication, Wiederkehr et al. (24) propose a transhepatic biliary catheterization before graft implantation. During graft harvesting, after parenchyma section, a wire guide is introduced in a retrograde fashion into the bile duct and exposed at the liver surface. A 4-F catheter is then attached to the wire guide, carefully pulled into the bile duct, placed through the anastomosis and kept as an external drainage for 7–14 days. Thereafter, a cholangiography is performed and if there is no evidence of biliary complication, the catheter is closed and kept in place until satisfactory postoperative recovery (30–90 days). No biliary complication was seen using this technique. However, the critical comments about this paper are that there is no control group and only few patients were reported (6 patients).

With regard to vascular outcomes, hepatic artery thrombosis and portal vein thrombosis are the most frequent complication countrywide, varying from 3.1–10.7% and 2.3–9.1%, respectively. Portal vein thrombosis is a particular concern in pediatric recipient, especially those with biliary atresia associated with portal vein sclerosis and hepatoduodenal ligament inflammation (25). In order to search risk factors associated with portal vein thrombosis in pediatric recipient, Neto et al. (13) performed a retrospective analysis of 486 primary LDLT procedures from October 1995 to May 2013. Vascular grafts used for portal reconstruction include living donor inferior mesenteric veins, living donor ovarian veins, recipient internal jugular veins, deceased donor iliac arteries and deceased donor iliac veins. Thirty-four patients (7.0%) developed portal veins thrombosis. However, over the years, its incidence decreased from 10.1% (between October 1995 and June 2004) to 2% (between March 2011 and May 2013) (P=0.07). During the same period, the use of vascular graft increased from 3.5% to 37.1% (P<0.001). Still, the authors concluded, in multivariate analysis, that vascular grafts remained the only independent risk factor for portal vein thrombosis.

Hepatic vein stenosis, with an incidence of 0.8–4.9%, is a less common vascular complication in Brazil (10-12). However, hepatic vein outflow block is a critical problem because its surgical repair is troublesome (26). Indeed, this is a particular issue in pediatric LDLT because of hepatic veins diameter and the potential risk of graft twist at anastomosis, especially after piggyback technique was introduced (27). Tannuri et al., in a retrospective analysis of 116 consecutive pediatric LDLT, compared three different hepatic vein reconstruction techniques: direct anastomosis between donor hepatic veins and recipient hepatic veins (group 1, 26 patients); triangular anastomosis at the confluence of all recipient hepatic veins, as proposed by Emond et al. (28) and Broelsch et al. (29) (group 2, 43 patients); and a new technique which consists of a wide longitudinal anastomosis performed at the anterior wall of inferior vena cava (group 3, 47 patients). In group 1 and 2, hepatic vein outflow block was seen in 27.7% and 5.7%, respectively (P=0.001). In group 3, no patient presented hepatic vein outflow block. No significant difference was noted between group 2 and 3 (P=0.41).

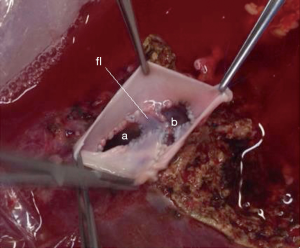

What concerns hepatic vein reconstruction in adult LDLT, our protocol is to harvest the right lobe including the middle hepatic vein, which adds no morbidity to the donor (30). The surgery is performed as already standardized, without pedicle clamping. During the back-table work, a venoplasty is performed in the right and middle hepatic veins, cutting the median edge of each vein vertically in order to enlarge the diameter. Two pieces of deceased iliac vein graft are used for reconstruction. One piece to perform a “new floor” between the veins and another one to perform a new common vein outlet by suturing the vein graft around the free edges of the hepatic veins (Figure 6). This is possible because our center does also DDLT and has a vessels graft bank, allowing us to use it in LDLT procedures.

Donor safety is the major issue in any solid organ living transplantation. Despite all the concern and care, liver living donors experience a relatively high-risk morbidity, as high as 67%, and a not negligible mortality, even in the most well-qualified and high-volume centers (31-36). Therefore, donor selection is the most important issue related to LDLT. In a donor evaluation protocol consisted age between 18 and 50 y, body mass index under 30 kg/m2, no previous abdominal upper surgery, blood test, chest X-ray and abdominal Doppler ultrasound, Araújo et al. (37) reported that 63.7% of potential donors were refused. Withdraw was the first cause of exclusion corresponding to 38.9% and 31% of adult and pediatric potential donors, respectively.

Overall, Brazilian liver living donor morbidity rate varies between 12.4% and 28.3% (10,16-18). Most of them are minor complications, as abdominal pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, minor bile leaks and superficial surgical site infection. Biliary fistula accounts for 3.7% to 8.3% and up to 20% of them need any kind of invasive treatment, which represent Dido-Clavien classification grade III. Among others grade III complications, one case of biliary stenosis had been reported (18). Still, one case of perforated duodenal ulcer that progressed to septic shock and multiple organ failure had also been reported by a national center (17). This donor was discharged on 68th PO with hemiparesis secondary to severe hypotension and cerebral ischemia. We also experienced a high volume biliary fistula in a donor, which was treated by endoscopic stent. Brazilian national mortality rate for LDLT is 0.14% (9), comparable to worldwide prevalence donor mortality of 0.2% (38).

Conclusions

LDLT programs in Brazil have low morbidity and mortality rates, with good outcome results. Hence, they enhance international experience that this is a feasible and safe procedure, as well as an excellent alternative strategy to overcome organs shortage. However, LDLT programs must be well planned and all the steps managed carefully, because one failure can compromise all the programs national and worldwide.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Bismuth H. Revisiting liver anatomy and terminology of hepatectomies. Ann Surg 2013;257:383-6. [PubMed]

- Olthoff KM, Emond JC, Shearon TH, et al. Liver regeneration after living donor transplantation: adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation cohort study. Liver Transpl 2015;21:79-88. [PubMed]

- Dagradi A, Munari PF, Gamba A, et al. Problems of surgical anatomy and surgical practice studied with a view to transplantation of sections of the liver in humans. Chir Ital 1966;18:639-59. [PubMed]

- Smith B. Segmental liver transplantation from a living donor. J Pediatr Surg 1969;4:126-32. [PubMed]

- Raia S, Nery JR, Mies S. Liver transplantation from live donors. Lancet 1989;2:497. [PubMed]

- Strong RW, Lynch SV, Ong TH, et al. Successful liver transplantation from a living donor to her son. N Engl J Med 1990;322:1505-7. [PubMed]

- Lobritto S, Kato T, Emond J. Living-donor liver transplantation: current perspective. Semin Liver Dis 2012;32:333-40. [PubMed]

- Yang X, Gong J, Gong J. The value of living donor liver transplantation. Ann Transplant 2012;17:120-4. [PubMed]

- Data from Brazilian Organ Transplantation Association. Available online: http://www.abto.org.br [database on the Internet]. Accessed on March 5, 2015.

- Tannuri AC, Gibelli NE, Ricardi LR, et al. Living related donor liver transplantation in children. Transplant Proc 2011;43:161-4. [PubMed]

- Steinbrück K, Enne M, Fernandes R, et al. Vascular complications after living donor liver transplantation: a Brazilian, single-center experience. Transplant Proc 2011;43:196-8. [PubMed]

- Neto JS, Pugliese R, Fonseca EA, et al. Four hundred thirty consecutive pediatric living donor liver transplants: variables associated with posttransplant patient and graft survival. Liver Transpl 2012;18:577-84. [PubMed]

- Neto JS, Fonseca EA, Feier FH, et al. Analysis of factors associated with portal vein thrombosis in pediatric living donor liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl 2014;20:1157-67. [PubMed]

- Feier FH, Chapchap P, Pugliese R, et al. Diagnosis and management of biliary complications in pediatric living donor liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl 2014;20:882-92. [PubMed]

- Ferraz-Neto BH, Zurstrassen MP, Hidalgo R, et al. Results of urgent liver retransplantation in the state of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Transplant Proc 2006;38:1911-2. [PubMed]

- Andrade WC, Velhote MC, Ayoub AA, et al. Living donor liver transplantation in children: should the adult donor be operated on by an adult or pediatric surgeon? Experience of a single pediatric center. J Pediatr Surg 2014;49:525-7. [PubMed]

- Coelho JC, de Freitas AC, Matias JE, et al. Donor complications including the report of one death in right-lobe living-donor liver transplantation. Dig Surg 2007;24:191-6. [PubMed]

- Wiederkehr JC, Pereira JC, Ekermann M, et al. Results of 132 hepatectomies for living donor liver transplantation: report of one death. Transplant Proc 2005;37:1079-80. [PubMed]

- Steinbrück K, Fernandes R, Enne M, et al. Is there any difference between right hepatectomy and left lateral sectionectomy for living donors? as much you cut, as much you hurt? HPB (Oxford) 2010;12:684-7. [PubMed]

- Seda-Neto J, Godoy AL, Carone E, et al. Left lateral segmentectomy for pediatric live-donor liver transplantation: special attention to segment IV complications. Transplantation 2008;86:697-701. [PubMed]

- Fernandes R, Pacheco-Moreira LF, Enne M, et al. Surgical complications in 100 donor hepatectomies for living donor liver transplantation in a single Brazilian center. Transplant Proc 2010;42:421-3. [PubMed]

- Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240:205-13. [PubMed]

- Carlisle EM, Testa G. Adult to adult living related liver transplantation: where do we currently stand? World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:6729-36. [PubMed]

- Wiederkehr JC, Lemos IM, Avilla SG, et al. Transhepatic biliary catheterization before graft implant in living donor liver transplantation. Transplant Proc 2005;37:1124-5. [PubMed]

- Takahashi Y, Nishimoto Y, Matsuura T, et al. Surgical complications after living donor liver transplantation in patients with biliary atresia: a relatively high incidence of portal vein complications. Pediatr Surg Int 2009;25:745-51. [PubMed]

- Sato Y, Yamamoto S, Takeishi T, et al. New hepatic vein reconstruction by double expansion of outflow capacity of left-sided liver graft in living-donor liver transplantation. Transplantation 2003;76:882-4. [PubMed]

- Tannuri U, Mello ES, Carnevale FC, et al. Hepatic venous reconstruction in pediatric living-related donor liver transplantation--experience of a single center. Pediatr Transplant 2005;9:293-8. [PubMed]

- Emond JC, Heffron TG, Whitington PF, et al. Reconstruction of the hepatic vein in reduced size hepatic transplantation. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1993;176:11-7. [PubMed]

- Broelsch CE, Whitington PF, Emond JC, et al. Liver transplantation in children from living related donors. Surgical techniques and results. Ann Surg 1991;214:428-37; discussion 437-9. [PubMed]

- Mancero JM, Gonzalez AM, Ribeiro MA Jr, et al. Living donor right liver lobe transplantation with or without inclusion of the middle hepatic vein: analysis of complications. World J Surg 2011;35:403-8. [PubMed]

- Brown RS Jr, Russo MW, Lai M, et al. A survey of liver transplantation from living adult donors in the United States. N Engl J Med 2003;348:818-25. [PubMed]

- Umeshita K, Fujiwara K, Kiyosawa K, et al. Operative morbidity of living liver donors in Japan. Lancet 2003;362:687-90. [PubMed]

- Middleton PF, Duffield M, Lynch SV, et al. Living donor liver transplantation--adult donor outcomes: a systematic review. Liver Transpl 2006;12:24-30. [PubMed]

- Pascher A, Sauer IM, Walter M, et al. Donor evaluation, donor risks, donor outcome, and donor quality of life in adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2002;8:829-37. [PubMed]

- Hwang S, Lee SG, Lee YJ, et al. Lessons learned from 1,000 living donor liver transplantations in a single center: how to make living donations safe. Liver Transpl 2006;12:920-7. [PubMed]

- Zhong J, Lei J, Wang W, et al. Systematic review of the safety of living liver donors. Hepatogastroenterology 2013;60:252-7. [PubMed]

- Araújo CC, Balbi E, Pacheco-Moreira LF, et al. Evaluation of living donor liver transplantation: causes for exclusion. Transplant Proc 2010;42:424-5. [PubMed]

- Cheah YL, Simpson MA, Pomposelli JJ, et al. Incidence of death and potentially life-threatening near-miss events in living donor hepatic lobectomy: a world-wide survey. Liver Transpl 2013;19:499-506. [PubMed]