Endometrial stromal sarcoma presenting as large bleeding left upper quadrant mass

Introduction

Endometrial stromal tumors can be classified into three categories: endometrial stromal nodules, endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) and undifferentiated ESS (1). ESSs are rare, comprising only approximately 0.2% of all uterine malignancies with an annual incidence of 1-2 per million women (2). Even fewer cases have been reported on patients presenting with symptomatic disease. We report the case of an ESS in a young lady presenting with a large bleeding abdominal mass.

Clinical case

A 29-year-old African-American woman presented to the emergency department with complaints of abdominal pain, anorexia and weight loss. A CT scan revealed a mass that measured over 24 cm in the left upper quadrant that extended into the mid-abdomen and pelvis. The mass abutted the greater curvature of the stomach; it had heterogeneous density with soft tissue components, neo-vascularity and elements of hemorrhage (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis included malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) arising from the stomach, retroperitoneal sarcoma (RPS), medullary carcinoma of the left kidney, and renal angiomyolipoma. Because the clinical suspicion of a GIST or RPS was highest, a needle biopsy was performed but was not diagnostic.

One week later a repeat biopsy was scheduled, however the patient presented at that time with worsening left upper quadrant pain radiating to the flank, associated with nausea, vomiting, night sweats, and fatigue. She was tachycardic and her hemoglobin was 5.5 g/dL. The patient was urgently admitted to the intensive care unit, transfused, and stabilized. The patient was taken to the angiography suite where an on table CT confirmed a rupture, bleeding tumor. Embolization of the tumor mass, including occlusion of multiple feeding vessels from the left renal artery, was performed. After further stabilization and optimization, the patient was taken to the operating room 2 days later. At the time of surgery, the mass involved multiple intra-abdominal structures and had ruptured through the transverse mesocolon with old blood in the pelvis. An en bloc excision of the mass with a partial pancreatectomy, splenectomy, transverse colectomy, left nephrectomy, left adrenalectomy and resection of the diaphragm was performed.

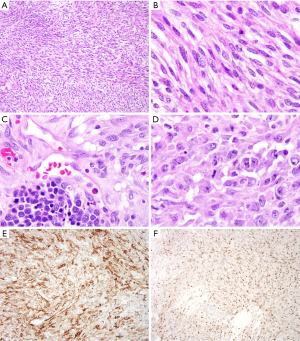

The final pathology revealed a malignant spindle and epithelial cell neoplasm with features favoring a variant of ESS. Most of the tumor had features of low-grade malignant spindle cell neoplasm. Some areas with greater nuclear atypia, mitotic index of up to 15 in 10 high power fields and epitheloid features as well as the presence of necrosis suggest a higher grade component. This morphology and the diffuse expression of CD10 with variable estrogen receptor (ER) expression were characteristic of ESS with low-grade and high-grade components. On immunohistochemistry the tumor was focally positive for Cyclin-D1, BCL-2 and CD99, while it was negative for progesterone receptor, EMA, AE/AE3, CAM5.2, PAX8, Inhibin, C-Kit, DOG-1, Melan-A, SOX10, GFAP, CD21, desmin, MDM2, Myogenin, CD34, MUC4, SMA, HMB45, ALK, S100 and beta-catenin (Figure 2).

The patient was referred to gynecologic oncology. She had a normal pelvic physical exam, as well as a pelvic MRI that demonstrated no evidence of a primary uterine tumor. Due to the concern of an occult primary uterine cancer, a hysterectomy was recommended, as well as adjuvant chemotherapy with hormonal therapy.

Discussion

The differential diagnosis of left upper quadrant tumors typically should include GIST, RPS, or lesions involving the pancreas, adrenal or kidney. Given the size, location, and involvement of other structures, obtaining a preoperative diagnosis may be helpful. Specifically, patients diagnosed with advanced GIST or RPS tumors may benefit from neo-adjuvant treatment (3,4). Other diagnostic possibilities included medullary renal cancer, which can be associated with sickle cell anemia (5), or AML, which can present with retroperitoneal hemorrhage known as Wunderlich syndrome (6).

ESS is one of the rarest gynecological tumors, representing only 0.2% of all uterine cancers. While the risk factors associated with ESS are poorly defined, African-American women have been noted to be 2 times more likely to get these rare uterine cancers (7). While women with primary ESS may present with pelvic pain and uterine bleeding, “extra-uterine” ESS is a much more uncommon initial presentation of disease. Moreover, the retroperitoneal hemorrhage is another uncommon manifestation for ESS. The prognosis of patients with ESS can be varied. Patients with ESS can be low-grade, which tends to be indolent, or high-grade (as in the current case), which can be more aggressive. Adjuvant therapy typically may include hormone therapy with medroxy progesterone, tamoxifen, gonadotropin releasing hormone analogues and aromatase inhibitors (8).

This case highlights how ESS can present in an atypical fashion as an intra-abdominal mass, as well as the importance of a multi-disciplinary treatment approach for patients with this disease.

Teaching points:

- The differential diagnosis a left upper quadrant mass typically should include GIST, RPS, or lesions involving the pancreas, adrenal or kidney. ESS can, however, present as an intra-abdominal mass extending in the abdominal cavity;

- Patients with a bleeding intra-abdominal mass are often served best with stabilization, embolization of the bleeding mass, and interval surgical resection;

- An interdisciplinary approach to patients with ESS is critical in managing this rare entity.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor-in-chief of this journal.

References

- Rauh-Hain JA, del Carmen MG. Endometrial stromal sarcoma: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122:676-83. [PubMed]

- Hendrickson MR, Tavassoli FA, Kempson RL, et al. Mesenchymal tumors and related lesions. In: Tavassoli FA, Devilee P, editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumors. Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of the Breast and Female Genital Organs. Lyon: IARC Press, 2003:233-44.

- Yang W, Yu J, Gao Y, et al. Preoperative imatinib facilitates complete resection of locally advanced primary GIST by a less invasive procedure. Med Oncol 2014;31:133. [PubMed]

- Pawlik TM, Vauthey JN, Abdalla EK, et al. Results of a single-center experience with resection and ablation for sarcoma metastatic to the liver. Arch Surg 2006;141:537-43; discussion 543-4. [PubMed]

- Daher P, Bourgi A, Riachy E, et al. Renal medullary carcinoma in a white adolescent with sickle cell trait. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2014;36:e285-9. [PubMed]

- Bissler JJ, Kingswood JC. Renal angiomyolipomata. Kidney Int 2004;66:924-34. [PubMed]

- Sherman ME, Devesa SS. Analysis of racial differences in incidence, survival, and mortality for malignant tumors of the uterine corpus. Cancer 2003;98:176-86. [PubMed]

- Linder T, Pink D, Kretzschmar A, et al. Hormone treatment of endometrial stromal sarcomas: A possible indication for aromatase inhibitors. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:abstr 9057.