Synchronous occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma and multiple biliary hamartomas mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma with multiple intra-hepatic metastases

A 67-year-old man was admitted to our hospital for a space-occupying lesion in his liver found 1 week earlier. There were no obvious complaints in this patient and no obvious abnormalities were founded during the physical examination. He presented with a habit of heavy drinking (500 mL/day) for more than 40 years. There was no history of other neoplasms, no other history of past illness or any family illness in this patient.

The tests for liver function were normal. His serum AFP was 1.7 ng/mL (normal, <20 ng/mL). The levels of other tumor markers, including carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA125), CA199, and prostate-specific antigen (PSA), were within normal limits. He was positive for serum hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antigen. Repeat testing for HBV DNA was below the detection value.

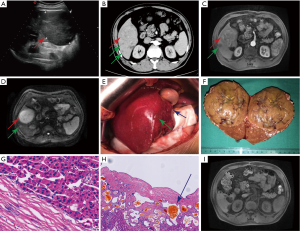

Abdominal US indicated a well-defined, hypoechoic mass (9.4×8.6 cm) found in the liver, with multiple well-defined mixed heterogenic echoic structures (Figure 1A).

Abdominal enhanced CT and MRI revealed a space-occupying lesion in liver segments V and VI, which showed obvious enhancement during the arterial phase and relatively receded during the portal and delayed phases compared to the surrounding liver parenchyma, with multiple lesions presenting similar enhancement patterns to that of the lesion (Figure 1B,C). Magnetic resonance diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) revealed high signal intensity with a nonuniform internal signal (Figure 1D).

The patient was diagnosed with HCC with multiple intra-hepatic metastases. Considering the multiple lesions in the liver, it is difficult to obtain biopsies. Finally, to verify the diagnosis, we performed an exploratory laparotomy and a subsequent complete resection of liver segments V and VI (Figure 1E,F). Histopathologically, this liver lesion revealed HCC. Immunohistochemical examination revealed CD34, GPC-3, CD7, HEP positivity, and AFP, CK19 negativity. Meanwhile, histopathological examination of multiple small lesions in the liver revealed biliary hamartomas (BHs) (Figure 1G,H).

Based on the results of the histopathological examination, the final diagnosis was modified to synchronous occurrence of HCC and multiple BHs. The patient’s recovery after the operation was uneventful and he was discharged on the ninth postoperative day. On review after 3 months, MRI re-examination showed that the sporadic lesions had not significantly changed, consistent with our diagnosis (Figure 1I).

Biliary hamartomas (BHs), also known as von Meyenburg complexes (VMCs), are rare benign liver lesions usually histologically characterized by congenital malformed bile ducts and surrounding fibrous stroma, which were first described by von Meyenburg in 1918 (1). Their prevalence ranges from 0.6% to 2.8% in the general population. In general, BHs are considered a consequence of congenital malformations of the bile ducts or the interrupted remodeling of the ductal plates during the embryological development of small intra-hepatic bile ducts (2).

In most cases, BHs are typically asymptomatic, single or multiple, and incidentally discovered. Rare patients with BHs admitted for symptoms including fever, jaundice, and abdominal pain (3,4).

BHs can be diagnosed via typical imaging features: hypoechoic, hyperechoic or mixed heterogenic echoic structures on US; lesions with low attenuation with irregular margins on plain CT, with rare enhancement during the arterial phase on dynamic contrast-enhanced CT and MRI (5,6). Overall, the combined analysis of US, CT, and MRI are essential and sufficient for the diagnosis of BHs. However, benign lesions in the liver may deceive surgeons by appearing as malignant tumors on imaging. Untypical images of BHs may also be misdiagnosed as liver metastatic disease, microabscesses, diffuse primary HCC, biliary cysts, or Caroli’s disease (1,6).

In addition, there are sporadic reports of hepatic malignancies on a background of BHs, including HCC and cholangiocarcinoma (7,8). However, it remains unclear whether the development of hepatic malignancies was epiphenomena unrelated to BHs or if BHs may progress to hepatic malignancies. Hence, regular examination is necessary for patients with BHs. Histopathological examination remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of BHs. Liver needle biopsies and exploratory laparotomy, if necessary, are helpful for the diagnosis of BHs (6).

It is widely accepted that patients who are asymptomatic and with no evidence to deteriorate with BHs do not necessarily require treatment but regular examination (2). However, several researchers have proposed positive surgical intervention. For example, Yang et al. preferred surgical treatment for BHs considering the possibility of deterioration (9).

In our case, according to the preoperative imaging findings, a clinical diagnosis of HCC with multiple intra-hepatic metastases was made. On this basis, the patient required immediate treatment and the therapeutic strategy differed from that for single HCC. However, the patient lacked the typical symptoms, including abdominal distension and pain, fever, weight loss, jaundice, and liver cirrhosis. Moreover, HCC combined with multiple intra-hepatic metastases usually comes with the elevation of the AFP. Finally, to verify the diagnosis, we performed an exploratory laparotomy and a subsequent complete resection of liver segments V and VI. Histopathological examination of the liver lesion revealed HCC. Immunohistochemical examination of the HCC revealed CD34, GPC-3, CD7, HEP positivity and AFP, CK19 negativity. Meanwhile, histopathological examination of some of the small lesions revealed BHs. We finally diagnosed the patient with synchronous occurrence of HCC and multiple BHs. The accurate diagnosis of the patient obviated the subsequent chemoradiotherapy, which may cause serious complications and sequelae in a 67-year-old man in a weakened condition.

MRI re-examination after 3 months indicated no significant changes in the scattered lesions in the remaining liver, which further strengthened our diagnosis. To avoid lesion deterioration, we suggested that the patient should be intensively followed-up with imaging and laboratory investigations. Additionally, although AFP level of the patient was within the normal range, we suggest paying increased attention to the dynamic AFP levels, which may indicate a deterioration.

In summary, it is necessary for surgeons to differentiate BHs with other liver lesions, especially in the co-existence of BHs and other liver lesions. Biopsies obtained by all means, if necessary, are helpful for the diagnosis of BHs. It is widely accepted that BHs without evidence to deteriorate do not necessarily require treatment but regular examination.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://hbsn.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/hbsn.2020.03.01/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Zheng RQ, Zhang B, Kudo M, et al. Imaging findings of biliary hamartomas. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:6354-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Raynaud P, Tate J, Callens C, et al. A classification of ductal plate malformations based on distinct pathogenic mechanisms of biliary dysmorphogenesis. Hepatology 2011;53:1959-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shi QS, Xing LX, Jin LF, et al. Imaging findings of bile duct hamartomas: a case report and literature review. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015;8:13145-53. [PubMed]

- Gupta V, Makharia G. Von Meyenburg complexes in a patient with obstructive jaundice. Med J Aust 2017;207:239. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wohlgemuth WA, Böttger J, Bohndorf K. MRI, CT, US and ERCP in the evaluation of bile duct hamartomas (von Meyenburg complex): a case report. Eur Radiol 1998;8:1623-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lev-Toaff AS, Bach AM, Wechsler RJ, et al. The radiologic and pathologic spectrum of biliary hamartomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1995;165:309-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tominaga T, Abo T, Kinoshita N, et al. A variant of multicystic biliary hamartoma presenting as an intrahepatic cystic neoplasm. Clin J Gastroenterol 2015;8:162-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heinke T, Pellacani LB, Costa Hde O, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in association with bile duct hamartomas: report on 2 cases and review of the literature. Ann Diagn Pathol 2008;12:208-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang XY, Zhang HB, Wu B, et al. Surgery is the preferred treatment for bile duct hamartomas. Mol Clin Oncol 2017;7:649-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]